poplar-heap is a collection of heap algorithms programmed in C++14 whose signatures more or less conrrespond to those of the standard library's heap algorithms. However, they use what is known as a "poplar heap" instead of a traditional binary heap to store the data. A poplar heap is a data structure introduced by Coenraad Bron and Wim H. Hesselink in their paper Smoothsort revisited. We will first describe the library interface, then explain what a poplar heap is, and how to implement and improve the usual heap operations with poplar heaps.

Now, let's be real: compared to usual binary heap-based based functions, poplar heap-based functions are slow. This library does not mean to provide performant algorithms. Its goals are different:

- Explaining what poplar heaps are

- Showing how poplar heaps can be implemented with O(1) extra space

- Showing that operations used in poplar sort can be decoupled

- Providing a proof-of-concept implementation

Note: while I didn't know about it when I created this project, what I describe here as a poplar heap has apparently already been described as a post-order heap by Nicholas J. A. Harvey & Kevin C. Zatloukal. The space and time complexities described in their paper match those of poplar heap (at least theoretically, I did not formally prove the complexities of the different poplar heap algorithms), but there is still a difference between the two data structures: their post-order heap requires the storage of two additional integers to represent the state of the heap, while the algorithms I present here only need to know the size of the array used to store the poplar heap. On the other hand, they provide formal proofs to demonstrate the complexities of the different operations of a post-order heap while I was unable to come up with such formal proofs for the poplar heap (formal proofs are unfortunately not my domain).

The poplar-heap library provides the following function templates:

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

void push_heap(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Requires: The range [first, last - 1) shall be a valid poplar heap. The type of *first shall satisfy the

MoveConstructible requirements and the MoveAssignable requirements.

Effects: Places the value in the location last - 1 into the resulting poplar heap [first, last).

Complexity: At most log(last - first) comparisons.

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

void pop_heap(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Requires: The range [first, last) shall be a valid non-empty poplar heap. RandomAccessIterator shall satisfy the

requirements of ValueSwappable. The type of *first shall satisfy the requirements of MoveConstructible and of

MoveAssignable.

Effects: Swaps the highest value in [first, last) with the value in the location last - 1 and makes

[first, last - 1) into a poplar heap.

Complexity: O(log(last - first)) comparisons.

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

void make_heap(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Requires: The type of *first shall satisfy the MoveConstructible requirements and the MoveAssignable

requirements.

Effects: Constructs a poplar heap out of the range [first, last).

Complexity: Theoretically O(last - first) comparisons (see issues #1 and #2).

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

void sort_heap(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Requires: The range [first, last) shall be a valid poplar heap. RandomAccessIterator shall satisfy the

requirements of ValueSwappable. The type of *first shall satisfy the requirements of MoveConstructible and of

MoveAssignable.

Effects: Sorts elements in the poplar heap [first, last).

Complexity: O(N log(N)) comparisons, where N = last - first.

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

bool is_heap(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Returns: is_heap_until(first, last, compare) == last.

template<

typename RandomAccessIterator,

typename Compare = std::less<>

>

RandomAccessIterator is_heap_until(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last,

Compare compare={});Returns: If (last - first) < 2, returns last. Otherwise, returns the last iterator it in [first, last] for

which the range [first, it) is a poplar heap.

Complexity: O(last - first) comparisons.

Poplar sort is a heapsort-like algorithm derived from smoothsort that builds a forest of specific trees named "poplars" before sorting them. The structure in described as follows in the original Smoothsort Revisited paper:

Let us first define a heap to be a binary tree having its maximal element in the root and having two subtrees each of which is empty or a heap. A heap is called perfect if both subtrees are empty or perfect heaps of the same size. A poplar is defined to be a perfect heap mapped on a contiguous section of the array in the form of two subpoplars (or empty sections) followed by the root.

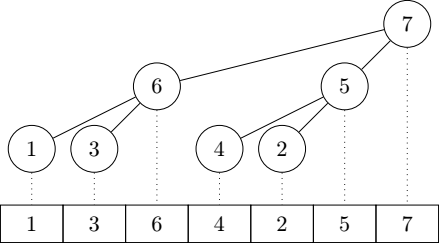

Because of its specific structure, we can already intuitively note that the size of a poplar is always a power of two minus one. This property is extensively used in the algorithm. The following graph represents a poplar containing seven elements, and shows how they are mapped to the backing array:

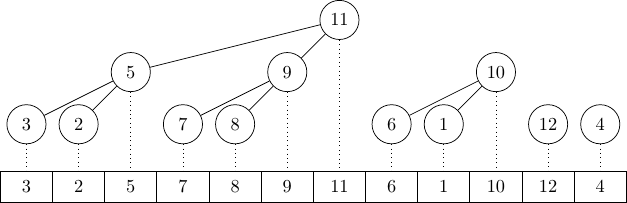

Now, let us define a "poplar heap" to be a forest of poplars organized in such a way that the bigger poplars come first and the smaller poplars come last. Moreover, the poplars should be as big as they possibly can. For example if a poplar heap contains 12 elements, it will be made of 4 poplars with respectively 7, 3, 1 and 1 elements. Two properties of poplar heaps described in the original paper are worth mentioning:

- There can't be more than O(log n) poplars in a poplar heap of n elements (Harvey & Zatloukal give an upper bound of at most ⌊log2(n + 1)⌋ + 1 poplars).

- Only the two rightmost poplars - the smallest ones - can have the same number of elements.

Another interesting property of poplar heaps is that a sorted collection is a valid poplar heap. One of the main ideas behind poplar sort was that an almost sorted collection would be faster to sort because constructing the poplar heap wouldn't move many elements around, while a regular heapsort can't take advantage of presortedness at all. We will see later that this property can actually be used to perform additional optimizations.

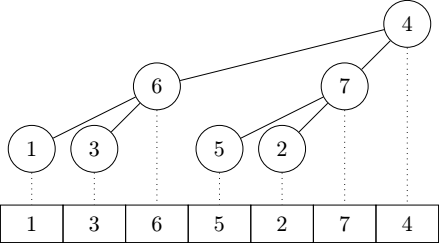

To handle poplars whose root has been replaced, Bron & Hesselink introduce the concept of semipoplar: a semipoplar has the same properties as a poplar except that its root can be smaller than the roots of its subpoplars. A semipoplar is mostly useful to represent an intermediate case when we are building a bigger poplar from two subpoplars and a root. Here is an example of a semipoplar:

A semipoplar can be transformed into a poplar thanks to a procedure called sift, which is actually pretty close from the equivalent procedure in heapsort: if the root of the semipoplar is smaller than that of a subpoplar, swap it with the bigger of the two subpoplar roots, and recursively call sift on the subpoplar whose root has been swapped until the whole thing becomes a poplar again. A naive C++ implementation of the algorithm would look like this (to avoid boilerplate, we don't template the examples on the comparison operators):

/**

* Transform a semipoplar into a poplar

*

* @param first Iterator to the first element of the semipoplar

* @param size Size of the semipoplar

*/

template<typename Iterator, typename Size>

void sift(Iterator first, Size size)

{

if (size < 2) return;

// Find the root of the semipoplar and those of the subpoplars

auto root = first + (size - 1);

auto child_root1 = root - 1;

auto child_root2 = first + (size / 2 - 1);

// Pick the bigger of the roots

auto max_root = root;

if (*max_root < *child_root1) {

max_root = child_root1;

}

if (*max_root < *child_root2) {

max_root = child_root2;

}

// If one of the roots of the subpoplars is bigger than that of the

// semipoplar, swap them and recursively call sift on this subpoplar

if (max_root != root) {

std::iter_swap(root, max_root);

sift(max_root - (size / 2 - 1), size / 2);

}

}As most heapsort-like algorithms, poplar sort is divided into two main parts:

- Turning the passed collection into a poplar heap

- Sorting the poplar heap

Be it the original poplar sort described by Bron & Hesselink or the revisited algorithm that I will describe later,

both are split into these two distinct phases. It should be possible to construct a poplar heap in O(n) time, but I

lack the knowledge required to prove it, so the instinctive analysis in the sections to come only try to demonstrate

a O(n log n) worst case for poplar::make_heap.

Note: if you're better than I am at formal proofs, you can visit this issue which dicusses whether

make_heap actually has a O(n) worst case.

The following animation by @aphitorite shows how poplar sort constructs and sorts a poplar heap:

The original poplar sort algorithm actually stores up to ⌊log2(n + 1)⌋ + 1 integers to represent the positions of the poplars. We will use (and store) the following small structure instead to represent a poplar in order to simplify the understanding of the algorithm while preserving the original logic as well as the original space and time complexities:

template<typename Iterator>

struct poplar

{

// The poplar is located at the position [begin, end) in the memory

Iterator begin, end;

// Unsigned integers because we're doing to perform bit tricks

std::make_unsigned_t<typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type> size;

auto root() const

-> Iterator

{

// The root of a poplar is always its last element

return std::prev(end);

}

};With that structure we can easily make an array of poplars to represent the poplar heap. Storing both the beginning, end and size of a poplar is a bit redundant, but it proved to be the fastest in my benchmarks: computing them over and over again apparently wasn't the best solution.

The poplar heap is constructed iteratively: elements are added to the poplar heap one at a time. Whenever such an element is added, it is first added as a single-element poplar at the end of the heap. Then, if the previous two poplars have the same size, both of them are combined in a bigger semipoplar where the new element serves as the root, and the sift procedure is applied to turn the new semipoplar into a full-fledged poplar. The first part of the poplar sort algorithm thus looks like this:

template<typename Iterator>

void poplar_sort(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

auto size = std::distance(first, last);

if (size < 2) return;

// Poplars forming the poplar heap

std::vector<poplar<Iterator>> poplars;

// Make a poplar heap

for (auto it = first ; it != last ; ++it) {

auto nb_pops = poplars.size();

if (nb_pops >= 2 && poplars[nb_pops-1].size == poplars[nb_pops-2].size) {

// Find the bounds of the new semipoplar

auto begin = poplars[nb_pops-2].begin;

auto end = std::next(it);

auto poplar_size = 2 * poplars[nb_pops-2].size + 1;

// Fuse the last two poplars and the new element into a semipoplar

poplars.pop_back();

poplars.pop_back();

poplars.push_back({begin, end, poplar_size});

// Turn the new semipoplar into a full-fledged poplar

sift(begin, poplar_size);

} else {

// Add the new element as a single-element poplar

poplars.push_back({it, std::next(it), 1});

}

}

// TODO: sort the poplar heap

}Now that we have our poplar heap, it's time to sort it. Just like a regular heapsort it's done by popping elements from the poplar heap one by one. Popping an element works as follows:

- Find the poplar with the biggest root

- Switch it with the root of the last poplar

- Apply the sift procedure to the poplar whose root has been taken to restore the poplar invariants

- Remove the last element from the heap

- If that element formed a single-element poplar, we are done

- Otherwise split the rest of the last poplar into two poplars of equal size

The first three steps are known as the relocate procedure in the original paper, which can be roughly implemented as follows:

template<typename Iterator>

void relocate(std::vector<poplar<Iterator>>& poplars)

{

// Find the poplar with the bigger root, assuming that there is

// always at least one poplar in the vector

auto last = std::prev(std::end(poplars));

auto bigger = last;

for (auto it = std::begin(poplars) ; it != last ; ++it) {

if (*bigger->root() < *it->root()) {

bigger = it;

}

}

// Swap & sift if needed

if (bigger != last) {

std::iter_swap(bigger->root(), last->root());

sift(bigger->begin, bigger->size);

}

}The loop to sort the poplar heap element by element (which replaces our previous TODO comment in poplar_sort) looks

like this:

// Sort the poplar heap

do {

relocate(poplars);

if (poplars.back().size == 1) {

poplars.pop_back();

} else {

// Find bounds of the new poplars

auto poplar_size = poplars.back().size / 2;

auto begin1 = poplars.back().begin;

auto begin2 = begin1 + poplar_size;

// Split the poplar in two poplars, don't keep the last element

poplars.pop_back();

poplars.push_back({begin1, begin2, poplar_size});

poplars.push_back({begin2, begin2 + poplar_size, poplar_size});

}

} while (not poplars.empty());And that's pretty much it for the original poplar sort. I hope that my explanation was understandable enough. If something wasn't clear, don't hesitate to mention it, open an issue and/or suggest improvements to the wording.

As I worked on poplar sort to try to make it faster, I noticed a few things and an idea came to my mind: would it be possible to make poplar sort run without storing an array of poplars, basically making it run with O(1) extra space and thus turning the poplar heap into an implicit data structure?

Even better: would it be possible to decouple the heap operations in order to reimplement the heap interface in the C++ standard library? Would it be possible to do so while keeping the current complexity guarantees of poplar sort and use O(1) space for every operation?

It turned out to be possible, as we will see in this section.

The procedure sift currently runs in O(log n) space: it can recursively call itself up to log(n) times before the semipoplar has been turned into a poplar, and every recursion makes the stack grow. On the other hand the recursive call only happens once as the last operation of the procedure, which basically makes sift a tail recursive function. An optimizing compiler might transform that into a loop, but we can also do that ourselves just to be extra sure:

template<typename Iterator, typename Size>

void sift(Iterator first, Size size)

{

if (size < 2) return;

auto root = first + (size - 1);

auto child_root1 = root - 1;

auto child_root2 = first + (size / 2 - 1);

while (true) {

auto max_root = root;

if (*max_root < *child_root1) {

max_root = child_root1;

}

if (*max_root < *child_root2) {

max_root = child_root2;

}

if (max_root == root) return;

using std::swap;

swap(*root, *max_root);

size /= 2;

if (size < 2) return;

root = max_root;

child_root1 = root - 1;

child_root2 = max_root - (size - size / 2);

}

}It was a pretty mechanical change, but we now have the guarantee that sift will run in O(log n) time and O(1) space. Considering that it is used in most poplar heap operations, it ensures that the space complexities of the other heap operations won't grow because of it.

My first idea was to make make_heap and sort_heap work in O(n log n) time like they do in a naive implementation of

heapsort: make_heap would iteratively push elements on the heap from first to last, and sort_heap would iteratively

pop elements from the heap from last to first. The functions could be implemented as follows:

template<typename Iterator>

void make_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

for (auto it = first ; it != last ; ++it) {

push_heap(first, it);

}

push_heap(first, last);

}

template<typename Iterator>

void sort_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

while (first != last) {

pop_heap(first, last);

--last;

}

}If we manage to implement both push_heap and pop_heap to run in O(log n) time with O(1) space, then make_heap and

and sort_heap will both run in O(n log n) time and O(1) space, making the whole poplar sort algorithm run with the

same time and space complexities.

Both push_heap and pop_heap require knowledge of the location of the main poplars forming the poplar heap. The

original poplar sort algorithm stores the positions of the poplars for that exact reason. In order to achieve that

without storing anything, we need to go back to the original properties of a poplar heap:

- The size of a poplar is always of the form 2^n-1

- The poplars are stored from the bigger to the smaller

- Poplars are always as big as they possibly can

Taking all of that into account, we can find the first poplar like this:

- It begins at the beginning of the poplar heap

- Its size is the biggest number of the form 2^n-1 which is smaller or equal to the size of the poplar heap

Once we have our first poplar, we can find the next poplar, then the ones after it by repeatedly applying that same

operation to the rest of the poplar heap. The following function can be used to find the biggest power of two smaller

than or equal to a given unsigned integer (sometimes called the bit floor of the number - it available in the

standard library since C++20 under the name std::bit_floor):

template<typename Unsigned>

Unsigned bit_floor(Unsigned n)

{

constexpr auto bound = std::numeric_limits<Unsigned>::digits / 2;

for (std::size_t i = 1 ; i <= bound ; i <<= 1) {

n |= (n >> i);

}

return n & ~(n >> 1);

}The function above works most of the time but only for unsigned integers. It is worth nothing that it also returns 0 when given 0 even though it's not a power of 2, just like its standard library counterpart. Given that function and the size of the poplar heap, the size of the first poplar can be found with the following operation:

auto first_poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;Interestingly enough, that operation works even when size is the biggest representable value of its type: since we

are only working with unsigned integers, size + 1u == 0 in this case since unsigned integers are guaranteed to wrap

around when overflowing. As we have seen before, our bit_floor implementation returns 0 when given 0, so retrieving

1 to that result will give back the original value of size back wrapping around once again. Fortunately the biggest

representable value of an unsigned integer type happens to be of the form 2^n-1, which is exactly what we expect. In

such a case there is a single poplar covering the whole poplar heap.

There are at most O(log n) poplars in a poplar heap, so iterating through all of them takes O(log n) time and O(1) space.

As we have seen with the original algorithm, pushing an element on a poplar heap requires to add that element at the end, then to form a new semipoplar and transform it if the previous two poplars have the same size. Since our poplar heap is implicit, all we actually have to do is to call sift if the size of the last poplar of the new poplar heap is greater than 1. We can use the technique described in the previous section to find the size of the last poplar in O(log n) time.

template<typename Iterator>

void push_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

// Make sure to use an unsigned integer so that bit_floor works correctly

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

// Find the size of the poplar that will contain the new element in O(log n) time

poplar_size_t last_poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

while (size - last_poplar_size != 0) {

size -= last_poplar_size;

last_poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

}

// Sift the new element in its poplar in O(log n) time

sift(std::prev(last, last_poplar_size), last_poplar_size);

}The size of the last poplar of the heap is found in O(log n) time, and sift runs in O(log n) time too. This makes the

push_heap procedure run in the expected O(log n) time and O(1) space, which means that we finally have a make_heap

implementation that runs in O(n log n) time and O(1) space.

pop_heap is actually very much like the relocate procedure from the original poplar sort algorithm, except that we

need to iterate the collection via the bit_floor trick instead of using stored iterators. On the other hand, since

we don't store anything, we don't have to reorganize poplars as the original algorithm does: finding biggest root the

heap, switching it with that of the last poplar, and calling sift on the resulting semipoplar is enough.

template<typename Iterator>

void pop_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

// Make sure to use an unsigned integer so that bit_floor works correctly

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

auto poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

auto last_root = std::prev(last);

auto bigger = last_root;

auto bigger_size = poplar_size;

// Look for the bigger poplar root

auto it = first;

while (true) {

auto root = std::next(it, poplar_size - 1);

if (root == last_root) break;

if (*bigger < *root) {

bigger = root;

bigger_size = poplar_size;

}

it = std::next(root);

size -= poplar_size;

poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

}

// Swap & sift if needed

if (bigger != last_root) {

std::iter_swap(bigger, last_root);

sift(bigger - (bigger_size - 1), bigger_size);

}

}Iterating through the roots runs in O(log n) time, and the sift procedure runs in O(log n) time too, which makes

pop_heap run in O(log n) time and O(1) extra space, which means that sort_heap runs in O(n log n) time and O(1)

space overall.

This is pretty much all we need to make poplar sort run in O(n log n) time and O(1) space, yet the most interesting part is that we managed to transform the poplar heap into an implicit data structure without worsening the complexity of its operations. On the other hand, the version that stores the iterators was consistently faster in my benchmarks, so the interest of the O(1) space version is mainly theoretical.

We have already reached our goal of making the poplar heap an implicit data structure, but there is still more to be said about it. This section contains both trivial improvements and more involved tricks to rewrite the heap operations. Some of the most interesting parts are alas unproven and empirically derived, but they consistently passed all of my tests and are worth mentioning anyway.

In the current state of things pop_heap computes the size of the sequence it is applied to every time it is called,

which is kind of suboptimal in sort_heap since we know the size to be one less at each iteration. A trivial

improvement is to pass it down from sort_heap instead of recomputing it every time:

template<typename Iterator>

void sort_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

if (size < 2) return;

do {

// Same as pop_heap except it doesn't compute the size

pop_heap_with_size(first, last, size);

--last;

--size;

} while (size > 1);

}The same improvement can be made to the current implementation of make_heap, but we have more interesting plans for

this function, so it will be left as an exercise to the reader.

One of my first ideas to implement make_heap without storing iterators was to implement the function in a top-down

fashion: we know the size of the poplar heap to build, which means that we know the size of the poplars that will

constitute that poplar heap. Looking at the previous algorithms highlights a new interesting property: the poplars

that will remain after the call to make_heap are actually independent of each other during construction time, which

means that we can build them separately.

How to make a poplar in a top-down fashion? The easiest solution is to recursively build the two subpoplars and sift the root, leading to a rather straightforward algorithm:

template<typename Iterator, typename Size>

void make_poplar(Iterator first, Size size)

{

if (size < 2) return;

make_poplar(first, size / 2);

make_poplar(first + size / 2, size / 2);

sift(first, size);

}Such an algorithm makes it easy to reuse one of the properties of poplars: a sorted collection is a valid poplar. It

turns out that, for small poplars, running a straight insertion sort is often faster in practice than recursively

calling make_poplar until the level of single-element poplars:

template<typename Iterator, typename Size>

void make_poplar(Iterator first, Size size)

{

if (size < 16) {

insertion_sort(first, first + size);

return;

}

make_poplar(first, size / 2);

make_poplar(first + size / 2, size / 2);

sift(first, size);

}The implementation of insertion sort is omitted here because it's irrelevant for the explanation, but you can still

find it in the source code of this repository. With such an algorithm, make_heap becomes an algorithm which iterates

through the poplars to build them directly:

template<typename Iterator>

void make_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

// Build the poplars directly without fusion

poplar_size_t poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

while (true) {

// Make a poplar

make_poplar(first, poplar_size);

if (size - poplar_size == 0) return;

// Advance to the next poplar

first += poplar_size;

size -= poplar_size;

poplar_size = bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

}

}While I like the straightforward aspect of building the final poplars directly in place, make_poplar actually uses

O(log n) extra space due to the double recursion, and can't be turned into a simple loop. This construction method is

unfortunately unsuitable to implement the poplar heap operations with O(1) extra space. However, its time complexity is

supposed to be O(n) instead of the original O(n log n) (see issue #2).

Another interesting property of this construction method is that it can easily be parallelized.

The make_heap implementation above made me want to try more things, namely to see whether I could find an iterative

make_heap algorithm that could still benefit from the insertion sort optimization. It felt like it was possible to

alternate building 15-element poplars and sifting other elements to make bigger poplar, but the logic behind that was

not obvious. At some point, I started to draw the following diagram with in mind the question "how many elements do I

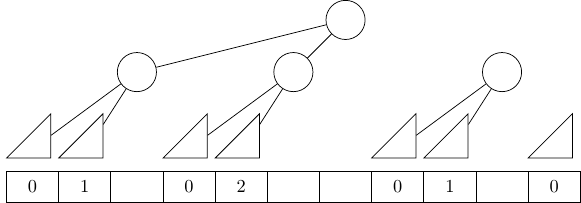

need to sift between each 15-element poplar?":

In the diagram above, you can find the global structure of the poplar heap as seen previously, but with a twist: the triangles represent 15-element poplars, the circles represent single elements, and the numbers below the triangles represent the number of elements to sift after the 15-element poplar above, considering that we sift every time two poplars of the same size preceed the element to sift. The sequence goes on like this: 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 3, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 4, 0, 1, etc. There seemed to be some logic that I did not understand, so looked it up on the internet and found that it corresponds to the beginning of the binary carry sequence, A007814 in the on-line encyclopedia of integer sequences. This specific sequence is also described as follows:

The sequence a(n) given by the exponents of the highest power of 2 dividing n

Following some empirical intuition, I designed a new make_heap algorithm as follows:

- Initialize a counter poplar_level with 1

- As long as the poplar heap isn't fully constructed, perform the following steps:

- Use insertion sort on the next 15 elements to make a poplar

- Perform the following operations log2(poplar_level) times:

- Consider the next element to be the root of a semipoplar whose size is twice the size of the previous poplar plus one

- Sift the root to turn the semipoplar into a poplar

- If there are fewer than 15 elements left in the collection, sort them with insertion sort and finish

- Otherwise increment poplar_level

I have no actual proof that the algorithm works and it doesn't feel super intuitive either, but I never managed to find

a sequence of elements that would make it fail up to this day. Here is the C++ implementation of that new make_heap,

using some bit tricks in the increment of the inner loop to avoid having to actually compute log2(poplar_level) the

expensive way:

template<typename Iterator>

void make_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

if (size < 2) return;

constexpr poplar_size_t small_poplar_size = 15;

if (size <= small_poplar_size) {

insertion_sort(first, last);

return;

}

// Determines the "level" of the poplars seen so far; the log2 of this

// variable will be used to make the binary carry sequence

poplar_size_t poplar_level = 1;

auto it = first;

auto next = std::next(it, small_poplar_size);

while (true) {

// Make a 15 element poplar

insertion_sort(it, next);

poplar_size_t poplar_size = small_poplar_size;

// Bit trick iterate without actually having to compute log2(poplar_level)

for (auto i = (poplar_level & -poplar_level) >> 1 ; i != 0 ; i >>= 1) {

it -= poplar_size;

poplar_size = 2 * poplar_size + 1;

sift(it, poplar_size);

++next;

}

if (poplar_size_t(std::distance(next, last)) <= small_poplar_size) {

insertion_sort(next, last);

return;

}

it = next;

std::advance(next, small_poplar_size);

++poplar_level;

}

}Interestingly enough, the variable small_poplar_size can be equal to any number of the form 2^n-1 and the algorithm

will still work, which means that setting it to 1 would give the most "basic" form of the algorithm, without the fancy

insertion sort optimization. The similarity between the original poplar heap graph and the one with 15-element poplars

already hinted at this result, which is most likely due to the recursive nature of the poplar structure.

This new make_heap algorithm was actually faster in my benchmarks than repeatedly calling push_heap, which might be

due to the insertion sort optimization, but also to the fact that computing the size of the current "last" poplar is

done in O(1) time instead of O(log n) time.

Ignoring the insertion sort optimization, this algorithm seems to perform O(log n) operations for each element, which gives an obvious upper bound of O(n log n) time and O(1) space for the whole algorithm. I could not formally prove it, but some similarities with binary heap construction make me feel this algorithm actually runs in O(n) time - see the corresponding issue for additional information.

make_heap probably runs in O(n) time, which means that sort_heap dominates the complexity when sorting a sequence

from scratch, so it naturally deserves the most attention when trying to find optimizations. I did not manage to find

a better algorithm without using extra memory for the job, but I was nevertheless able to obtain a 10~65% speedup when

sorting a collection of integers by optimizing bit_floor with compiler intrinsics.

The bit_floor implementation shown previously runs in O(log k) time when computing the bit floor of a k-bit unsigned

integer. Intrinsics make it possible to compute the bit floor in O(1) by computing the position of the highest set bit

and shifting a single bit to that position. The algorithm below shows how to compute the bit floor of an unsigned

integer with GCC and Clang intrinsics:

unsigned bit_floor(unsigned n)

{

constexpr auto k = std::numeric_limits<unsigned>::digits;

if (n == 0) return 0;

return 1u << (k - 1 - __builtin_clz(n));

}There are equivalent __builtin_clzl and __builtin_clzll intrinsics to handle the long and long long unsigned

integer types; handling even bigger types requires more tricks that aren't showed here but can be found in standard

library implementations of the C++20 function std::countl_zero.

Unfortunately the implementation above is often branchful (recent Clang implementations manage to optimize that branch

away on specific architectures with specific compiler flags), which is something we would rather avoid in the hot path

of the algorithm. I tried to come up with various bit tricks to get rid of the branch, but all the results were either

still branchful, undefined behaviour, or both at once. In the end I decided to introduce a new unguarded_bit_floor

function which does not always perform the check against zero:

template<typename Unsigned>

constexpr auto unguarded_bit_floor(Unsigned n) noexcept

-> Unsigned

{

return bit_floor(n);

}

#if defined(__GNUC__) || defined(__clang__)

constexpr auto unguarded_bit_floor(unsigned int n) noexcept

-> unsigned int

{

constexpr auto k = std::numeric_limits<unsigned>::digits;

return 1u << (k - 1 - __builtin_clz(n));

}

// Overloads for unsigned long and unsigned long long not shown here

#endifThe only place where we might call bit_floor with 0 in sort_heap is when the computed size is the biggest

representable value of its type, which can only ever happen at the very beginning of the sorting phase since we sort

fewer and fewer elements as the sort goes on. This means that we can call bit_floor once at the beginning before any

element has been sorted, and use unguarded_bit_floor everywhere else. To accomodate this change we need to compute

the bit floor in the sort_heap loop itself and pass it down to pop_heap_with_size explicitly:

template<typename Iterator>

auto sort_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

-> void

{

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

poplar_size_t size = std::distance(first, last);

if (size < 2) return;

auto poplar_size = detail::bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

do {

detail::pop_heap_with_size(first, last, size, poplar_size);

--last;

--size;

poplar_size = detail::unguarded_bit_floor(size + 1u) - 1u;

} while (size > 1);

}pop_heap_with_size has to be modified accordingly and can afford to only use unguarded_bit_floor internally, and

pop_heap also needs to be modified to accomodate the new interface of pop_heap_with_size. The function push_heap

can also be changed to use bit_floor once then unguarded_bit_floor in its inner loop.

While these functions are not needed to implement poplar sort, the C++ standard library also defines two functions to check whether a collection is already a heap:

std::is_heapchecks whether the passed collection is a heapstd::is_heap_untilreturns the iteratoritfrom the passed collection such as[first, it)is a heap

The function std::is_heap can generally be implemented by checking whether std::is_heap_until

returns last. The same logic works with a poplar heap:

template<typename Iterator>

bool is_heap(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

return is_heap_until(first, last) == last;

}The function is_heap_until can implemented by checking for every element whether it is bigger than the roots of both

of its subpoplars when said element has subpoplars. By checking it from first to last element we ensure that the any

element prior the current one is already part of a poplar heap, so we only need to check one level each time instead of

recursively checking every time that the poplar property holds for every level of a poplar. This makes for a sweet O(n)

algorithm that can be made to use only O(1) space by adapting the previous make_heap algorithm:

template<typename Iterator>

Iterator is_heap_until(Iterator first, Iterator last)

{

if (std::distance(first, last) < 2) {

return last;

}

using poplar_size_t = std::make_unsigned_t<

typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::difference_type

>;

// Determines the "level" of the biggest poplar seen so far

poplar_size_t poplar_level = 1;

auto it = first;

auto next = std::next(it);

while (true) {

poplar_size_t poplar_size = 1;

// The loop increment follows the binary carry sequence for some reason

for (auto i = (poplar_level & -poplar_level) >> 1 ; i != 0 ; i >>= 1) {

// Beginning and size of the poplar to track

it -= poplar_size;

poplar_size = 2 * poplar_size + 1;

// Check poplar property against child roots

auto root = it + (poplar_size - 1);

auto child_root1 = root - 1;

if (*root < *child_root1) {

return next;

}

auto child_root2 = it + (poplar_size / 2 - 1);

if (*root < *child_root2) {

return next;

}

if (next == last) return last;

++next;

}

if (next == last) return last;

it = next;

++next;

++poplar_level;

}

}In make_heap we could iterate over elements 15 by 15 because we had an optimization to handle 15 values at once. This

is not the case for this algorithm, so we fall back to using a single element at a time for poplar_size.

That's pretty much it for poplar heap: we have seen several ways to implement operations with different size complexities depending on the method used. We managed to decouple poplar heap operations and to implement them without intermediate state and with O(1) space complexity, actually lowering the space complexity of the poplar sort algorithm as described in the original paper by Bron & Hesselink. Such complexities were already demonstrated for the equivalent post-order heap by Nicholas J. A. Harvey & Kevin C. Zatloukal, but our implementation of poplar heap further reduces the need to store additional information to represent the state of the heap, requiring only the bounds of the region of storage where it lives.

If you have any questions, improvements or proofs to suggest, don't hesitate to open an issue on the project :)